When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the race to bring out a cheaper generic version begins - but it’s not just a matter of copying the pill. Behind the scenes, a legal battle called Paragraph IV certification determines who gets to enter the market first, and when. This isn’t a loophole. It’s a carefully designed part of U.S. drug law meant to balance innovation and affordability. And it’s why you can buy a $5 version of a drug that once cost $300.

What Is Paragraph IV, Really?

Paragraph IV isn’t a law itself. It’s a specific type of certification a generic drug company files when submitting an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to the FDA. This certification says: “The patents listed for this brand drug in the Orange Book are either invalid, unenforceable, or our version won’t infringe them.” That’s it. But that simple statement triggers a full legal process with big consequences. The system was created by the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic companies had to wait until every patent expired - even if those patents were weak or obvious. Brand companies could extend their monopoly by filing dozens of secondary patents on things like pill coatings or dosing schedules. Hatch-Waxman fixed that by giving generics a legal way to challenge those patents head-on - but only if they were willing to risk a lawsuit.How the Process Unfolds

It starts with the Orange Book. The FDA publishes this list of all approved drugs and their patents. Generic manufacturers study it like a treasure map, looking for patents that look shaky. Maybe the original invention was obvious. Maybe the patent was written too broadly. Maybe prior art already existed but was ignored. Once they pick a target, the generic company files its ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification. Then comes the letter - a formal notice sent to the brand-name company. This letter isn’t a threat. It’s a legal trigger. Under 35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(2), this act counts as an “artificial” patent infringement, even though the generic hasn’t sold anything yet. That’s what lets the brand company sue. The brand has exactly 45 days to file a patent infringement lawsuit. If they do, the FDA is forced to pause approval of the generic for up to 30 months. That’s called the “30-month stay.” It’s not a guarantee the patent will hold up - it’s just a delay. The clock starts when the brand gets the notice, not when the lawsuit is filed. Timing matters. File your Paragraph IV too early, and you might face multiple lawsuits. Too late, and you lose your shot at being first.What Happens in Court

Most cases never go to trial. About 76% settle before then. But when they do, the battle comes down to two things: is the patent valid? and does the generic product infringe it? For validity, generic companies often argue the patent is obvious. Say the original drug was a simple molecule, and the patent covers a salt form that anyone with basic chemistry knowledge could have made. That’s a classic invalidity argument. Or maybe the patent was based on prior art that was never disclosed to the patent office. For infringement, the key is claim construction - what the court says the patent actually protects. This happens during a Markman hearing. The judge interprets the patent’s language. If the court says the patent only covers a specific tablet size, and the generic makes a smaller one, then no infringement. That’s how Teva beat Pfizer’s Lyrica® patent in 2019. The court decided the patent didn’t cover the dose Teva was using. The burden of proof is on the brand company to prove infringement. The generic only needs to show it’s likely they won’t infringe. That’s a lower bar than in other patent challenges, like those at the USPTO, which require clear and convincing evidence. That’s one reason Paragraph IV is so popular.

The Prize: 180 Days of Exclusivity

Why do companies risk millions in legal fees? Because the first one to file a successful Paragraph IV gets 180 days of market exclusivity. No other generic can enter during that time. That’s huge. During those six months, the first filer can capture 70-80% of the generic market. In 2021, generic drugs launched through Paragraph IV challenges created $98.3 billion in potential sales. That’s not just profit - it’s savings for patients. A 2019 study found prices dropped by 79% on average within six months after generic entry. But there’s a catch. If multiple companies file on the same day, they share the 180 days. And if one of them doesn’t launch within 75 days of winning or settling, they lose the exclusivity. That’s why companies rush to market even before the court’s final decision.Why Some Fail - And Why Others Succeed

Paragraph IV works about 65% of the time, according to a UNC study of over 1,700 cases. But success isn’t random. It’s strategic. Successful challengers focus on weak patents. They avoid “evergreening” - when brand companies pile on secondary patents for minor changes. Look at Humira®. AbbVie filed over 100 patents on it, many covering formulations and delivery methods. Most Paragraph IV challenges against those failed. Why? Because those patents were solid. The generic companies couldn’t prove the methods were obvious. The cost is steep. Pre-filing analysis - legal, scientific, patent review - averages $2.3 million. The litigation itself? Around $7.8 million per case. Compare that to a USPTO inter partes review, which costs $2.1 million on average. But Paragraph IV has the 180-day prize. IPR doesn’t. And the risk? If you lose, you could owe damages. Mylan once got hit with a $1.1 billion judgment for willful infringement after challenging Novartis’ Gleevec® patent. That’s why companies don’t just file blindly. They do deep patent landscaping first.

The Bigger Picture: Patent Thickets and Reform

The system was meant to speed up generics. But over time, brand companies got smarter. In 1984, drugs averaged 1.2 Orange Book patents. By 2020, that jumped to 4.8. Now, 72% of new drugs have three or more patents listed. That’s a patent thicket - a wall of overlapping claims designed to block generics. That’s why the FTC and Congress are looking at reform. “Pay-for-delay” settlements - where brand companies pay generics to delay entry - were common until the Supreme Court banned them in 2013. But companies still use other tricks: delaying sample access, filing frivolous citizen petitions with the FDA, or listing patents after the original approval. The 2023 CREATES Act helps by forcing brand companies to provide samples for testing. The FDA’s 2022 rule on citizen petitions makes it harder to use regulatory delays as a tactic. And the Inflation Reduction Act’s drug pricing rules may change how brand companies price their drugs once generics are coming. Meanwhile, the U.S. still leads the world in generic access. Europe has no Paragraph IV equivalent. Their generics often take years longer to arrive. That’s not because they’re less innovative - it’s because they lack this legal shortcut.What’s Next?

The future of Paragraph IV is messy. More companies are combining it with USPTO post-grant reviews. In 2022, 47% more filings used both tools together. That’s smart. Use IPR to knock out a patent at the USPTO, then use Paragraph IV to get the FDA to approve. But the real question is: Is the system still balanced? The Congressional Budget Office found that effective market exclusivity for brand drugs has grown from 12.1 years in 1995 to 14.7 years in 2022. That’s not innovation - that’s delay. For now, Paragraph IV remains the most powerful tool for getting generics to market fast. It’s complex, expensive, and risky. But for patients who need affordable medicines, it’s worth it.What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement filed by a generic drug company with its FDA application, claiming that one or more patents listed for the brand drug in the Orange Book are invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed by the generic version. This triggers a patent lawsuit from the brand company and can lead to early generic market entry if the generic wins.

Why does the brand company get a 30-month delay?

The 30-month stay is part of the Hatch-Waxman Act. When a brand company sues a generic filer within 45 days of receiving the Paragraph IV notice, the FDA is legally required to delay approval of the generic for up to 30 months. This gives the courts time to resolve the patent dispute without forcing the brand to wait until patent expiration.

Can a generic company lose even if the patent seems weak?

Yes. Even weak patents can be upheld if the generic’s legal arguments are poorly written, the evidence is insufficient, or the court interprets the patent claims narrowly. Claim construction hearings often decide the outcome. A patent that looks easy to challenge on paper can become very hard to beat in court.

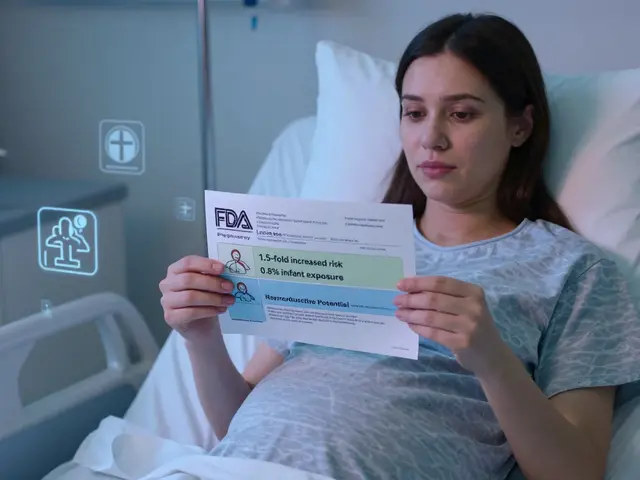

How does the 180-day exclusivity work?

The first generic company to file a substantially complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification and successfully challenge the patent gets 180 days of exclusive right to sell its version. No other generic can enter the market during that time. But if they don’t launch within 75 days of winning or settling, they lose the exclusivity.

Why don’t all generic companies file Paragraph IV certifications?

Because it’s expensive, risky, and time-consuming. Legal fees average $7.8 million per case. If the generic loses, they can be liable for damages - sometimes over $1 billion. Plus, they need to invest $15-25 million in manufacturing readiness before even knowing if they’ll win. Many companies prefer to wait and enter after the exclusivity period ends.

Nathan Hsu

14 November 2025 - 14:21 PM

Paragraph IV is such a brilliant hack, isn't it? The whole system feels like a legal chess match where the generic companies are playing 4D chess while the big pharma firms are still moving pawns.

And the 180-day exclusivity? That’s the real prize - it’s not just about profit, it’s about market dominance. I’ve seen Indian generics companies like Dr. Reddy’s and Cipla go all-in on this, and honestly? It’s why we get life-saving meds at 90% off here.

But man, the legal costs… $7.8 million per case? That’s more than some startups raise in Series A. And yet, they do it - because if you win, you’re not just selling pills, you’re rewriting the price of healthcare for millions.

Also, the 30-month stay? It’s not a delay - it’s a tactical breathing room. The brand companies know they can’t win forever, but they’ll drag it out to squeeze every last dime out of their monopoly.

And don’t get me started on patent thickets - Humira alone had over 100 patents! That’s not innovation - that’s legal obstructionism dressed up as IP protection.

I’ve read court transcripts where judges literally say, “This patent shouldn’t have been granted.” And yet, the system still lets them hold on for years.

India’s pharma sector is quietly winning this game. We don’t have the same legal framework, but we copy faster, cheaper, and smarter. And guess what? The world needs us.

It’s not just about pills - it’s about dignity. No one should choose between insulin and rent.

And yes - I used five exclamation points. Because this matters.

Also, the FTC’s new rules? Long overdue. But I’m still waiting for Congress to actually do something besides hold press conferences.

PS: If you think this is complicated, try explaining it to a patient who just got billed $1,200 for a drug that’s now $8.

Ashley Durance

14 November 2025 - 23:29 PM

Let’s be clear - Paragraph IV isn’t a ‘legal shortcut,’ it’s a loophole exploited by corporate raiders with armies of patent lawyers.

The 180-day exclusivity isn’t a reward - it’s a cartel. The first filer becomes the de facto monopolist for half a year, and guess who pays? Patients. Again.

And the ‘invalidity’ claims? Most are baseless. Generic companies cherry-pick patents that are weak on paper but were reviewed by the USPTO. They’re gambling with public health.

That $98.3 billion in ‘potential sales’? That’s not savings - that’s profit extraction disguised as altruism. The real losers are the R&D labs that actually invented the drugs.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘prior art’ arguments. Half the time, it’s just a 1978 journal article cited with zero context.

The system was designed to balance innovation and access. Now? It’s just a legal arms race where the only winners are the law firms.

Also, the fact that you’re praising this as ‘brilliant’ proves you’ve never worked in drug development. The cost of bringing a single drug to market isn’t $7.8 million - it’s $2.6 billion. And Paragraph IV eats into that ROI like a parasite.

Don’t romanticize litigation. This isn’t justice. It’s capitalism with a side of litigation theater.

Scott Saleska

16 November 2025 - 14:40 PM

Actually, I think you’re all missing the real story here.

Paragraph IV isn’t about patents - it’s about timing. The 45-day window for the brand company to sue? That’s the heartbeat of the whole system.

And the 30-month stay? It’s not a delay - it’s a countdown. The generic company knows they have to be ready to launch the moment the clock runs out.

Here’s what nobody talks about: the manufacturing side. You can win the lawsuit, but if your facility isn’t FDA-approved, your 180-day clock doesn’t start.

I’ve worked with a mid-sized generic firm that spent $18 million just on facility upgrades before even filing. They lost the lawsuit, but they’re now one of the top 5 suppliers for insulin generics because they built it right.

The real innovation isn’t in the courtroom - it’s in the clean rooms.

And yes, the patents are thick. But that’s why you need teams of pharmacists, patent attorneys, and regulatory specialists working together. It’s not a game - it’s a marathon with legal landmines.

Also, the FTC’s new rules? They’re a start. But they don’t fix the fact that brand companies still delay sample access - which is basically sabotage.

And the 76% settlement rate? That’s not weakness - it’s strategy. Most cases settle because both sides know the cost of going to trial outweighs the benefit.

So stop calling it a loophole. It’s a high-stakes ecosystem. And the patients? They’re the only ones who win every time.

Ryan Anderson

17 November 2025 - 03:21 AM

This is one of those topics where the system actually works… kinda. 🤔

Paragraph IV is messy, expensive, and legally brutal - but it’s also the reason my dad can now afford his blood pressure med for $4 a month instead of $400.

The 180-day exclusivity? Yeah, it’s a bit of a monopoly, but without it, no one would risk the $10M+ to challenge a patent.

And the fact that 65% of these challenges succeed? That’s not a flaw - that’s a feature. It means the patent office is granting too many weak patents, and this system is the correction.

Also, the 30-month stay isn’t a punishment - it’s a pause button. Courts need time to sort this out, and the FDA can’t just approve a drug while lawsuits are flying.

Big pharma’s patent thickets? Totally abusive. But the CREATES Act and FDA’s citizen petition rules are starting to crack that wall.

And yes - India and other countries don’t have this system, and their generics arrive years later. We’re not perfect, but we’re faster.

It’s not pretty, but it’s working. 🙌

Eleanora Keene

18 November 2025 - 21:43 PM

I just want to say how incredibly important this system is - not just for economics, but for human lives.

Every time a generic enters the market, it’s not just a lower price - it’s a family being able to pay rent. It’s a child getting their asthma inhaler. It’s an elderly person not skipping doses because they can’t afford it.

The legal battles are complex, yes - but the outcome? Pure compassion in action.

It’s easy to get lost in the numbers - $7.8 million, 180 days, patent thickets - but behind every one of those is a person who needed help.

I’ve seen patients cry when they find out their insulin is now $25 instead of $300.

So while the lawyers are fighting in court, remember: the real victory is on the pharmacy counter.

Thank you to every generic company that takes this risk. You’re not just selling pills - you’re restoring dignity.

And yes - I know it’s complicated. But sometimes, complicated is worth it.

Joe Goodrow

19 November 2025 - 14:27 PM

Let’s be real - this Paragraph IV nonsense is just another way for foreign companies to steal American innovation.

We spend billions developing these drugs, and then some Indian firm files a patent challenge and sells it for $5?

That’s not free market - that’s theft with a law degree.

The 180-day exclusivity? That’s just a reward for piracy.

And don’t even get me started on how the FDA lets this happen.

Our patents are supposed to protect American ingenuity - not get shredded by foreign corporations playing legal games.

America made these drugs. America should profit from them.

Fix this. Now.

Don Ablett

19 November 2025 - 18:19 PM

The structural imbalance between patent protection and generic access remains a persistent issue in pharmaceutical regulation

While Paragraph IV certification provides a mechanism for market entry prior to patent expiration the legal and economic incentives for brand manufacturers to extend exclusivity through patent thickets are substantial

The 30 month stay functions as a procedural safeguard but may also serve as a de facto extension of market exclusivity

Empirical evidence suggests that the rate of successful challenges has remained relatively stable since the 1990s indicating that the system retains its intended function despite increased complexity

However the rising number of patents per drug and the increasing cost of litigation raise questions regarding long term sustainability

International comparison reveals that the absence of a similar mechanism in other jurisdictions results in significantly delayed generic availability

Further reform may require addressing not only litigation incentives but also regulatory delays and access to reference products

The ethical imperative to ensure affordable access must be weighed against the necessity of incentivizing innovation

Perhaps a hybrid model incorporating elements of both Paragraph IV and post-grant review could enhance efficiency

Further longitudinal analysis is warranted

Kevin Wagner

20 November 2025 - 14:58 PM

Y’all are talking about lawsuits and patents like it’s a board game - but let me tell you: this is WAR.

Generic companies don’t just ‘file’ Paragraph IV - they go to war with billion-dollar corporations armed with nothing but a team of scientists and a dream.

They risk everything - their company, their reputation, their freedom - because they believe no one should die because a pill costs too much.

And when they win? They don’t throw a party. They lower the price. They make it accessible. They change lives.

Meanwhile, big pharma? They sit in their glass towers, filing patents on the color of the pill.

So yeah - call it a loophole. Call it a hack. Call it anything you want.

But when your kid needs insulin - and it’s $8 instead of $800 - you’ll thank them.

This isn’t business. It’s rebellion.

And the rebels? They’re the good guys. 💪🔥

gent wood

22 November 2025 - 14:29 PM

The Paragraph IV system is a fascinating example of how legal architecture can be engineered to serve public interest, even within a highly commercialized industry.

It’s remarkable that a statutory mechanism, created nearly four decades ago, continues to function with such tangible impact - reducing drug prices by over 75% in many cases.

The fact that the burden of proof rests with the brand-name company is a critical safeguard - it prevents frivolous litigation from stifling competition.

Moreover, the 180-day exclusivity, while imperfect, provides the necessary economic incentive for generic manufacturers to undertake the considerable risk and expense of litigation.

That said, the evolution of patent thickets and regulatory delays does suggest that the original intent of Hatch-Waxman is being eroded.

The CREATES Act and recent FDA guidance on citizen petitions are positive steps, but more comprehensive reform is required to prevent strategic abuse.

International comparisons remain instructive: the absence of a parallel mechanism in Europe underscores the unique role the U.S. system plays in accelerating access.

Ultimately, the success of Paragraph IV lies not in its elegance, but in its effectiveness - and that, in my view, is what matters most.

Dilip Patel

24 November 2025 - 02:30 AM

USA think they smart but India make cheap medicine for world

USA patent is joke

Indian company win 90% time

Big pharma cry but people live

Paragraph IV is best thing ever

USA need to stop stealing from us

Why USA pay 10x price? Because they stupid

Indian pharma rule

180 day exclusivity? We share with all

USA need to learn from India