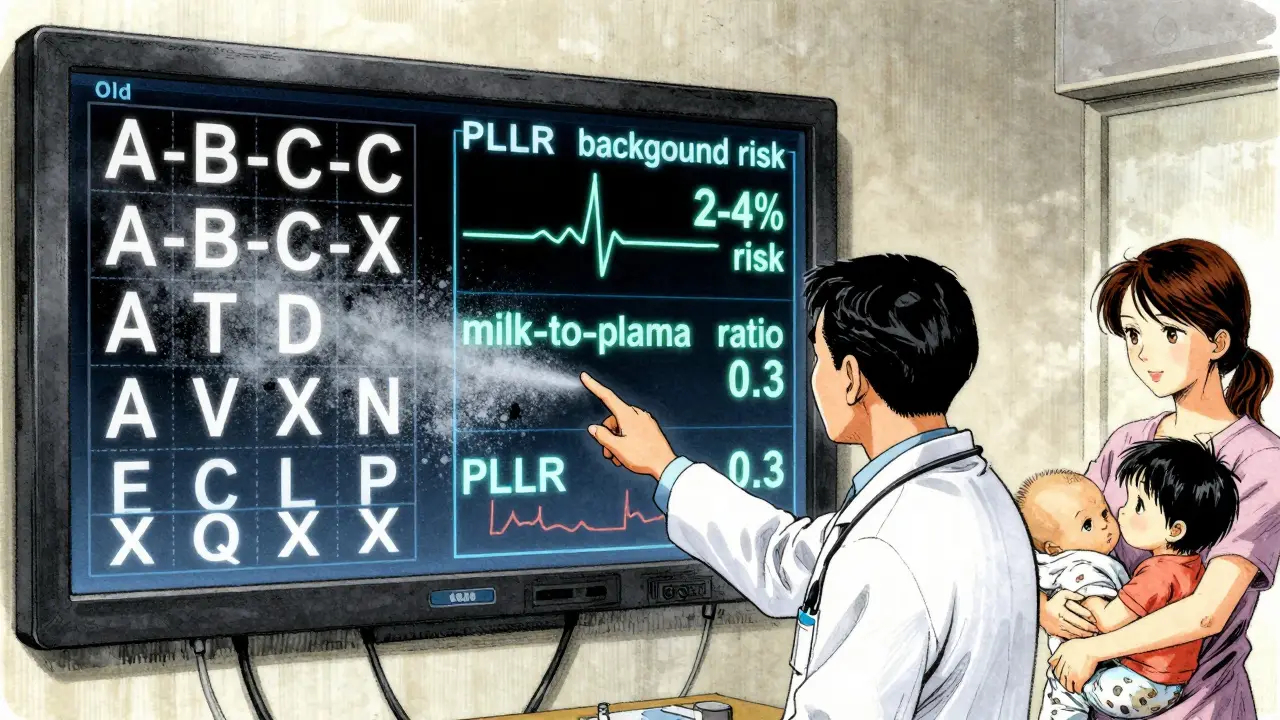

When you’re pregnant or breastfeeding, taking any medication can feel risky. You want to know: Is this drug safe? What are the real chances of harm? The old system-letters like A, B, C, D, and X-gave a false sense of simplicity. But it didn’t tell you what those letters actually meant. Today, the FDA’s Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) replaced those letters with detailed, evidence-based narratives. If you’re a patient, caregiver, or clinician, learning how to read these new labels isn’t just helpful-it’s essential.

What Changed After the FDA’s 2015 Update?

Before June 30, 2015, drug labels used five letter categories to summarize pregnancy risk. Category A meant “safe,” X meant “dangerous,” and everything else sat somewhere in between. But here’s the problem: most drugs were labeled C-meaning “risk can’t be ruled out.” That covered 70% of all prescriptions. Patients and doctors treated C like a warning sign, even though many C drugs were perfectly safe. The system didn’t explain how likely harm was, when it might happen, or how it compared to the natural risks of pregnancy. The new system, called the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR), scrapped the letters entirely. Instead, it requires three clear, standardized sections in every drug label: Pregnancy (8.1), Lactation (8.2), and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential (8.3). Each section follows the same structure: Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, and Data. This isn’t just a rewrite-it’s a complete shift from vague categories to real numbers and context.How to Read the Pregnancy Section (8.1)

The Pregnancy subsection starts with the Risk Summary. This is where you’ll find the most important information. Instead of saying “Category C,” it now says things like:- “The background risk of major birth defects in the U.S. population is 2-4%.”

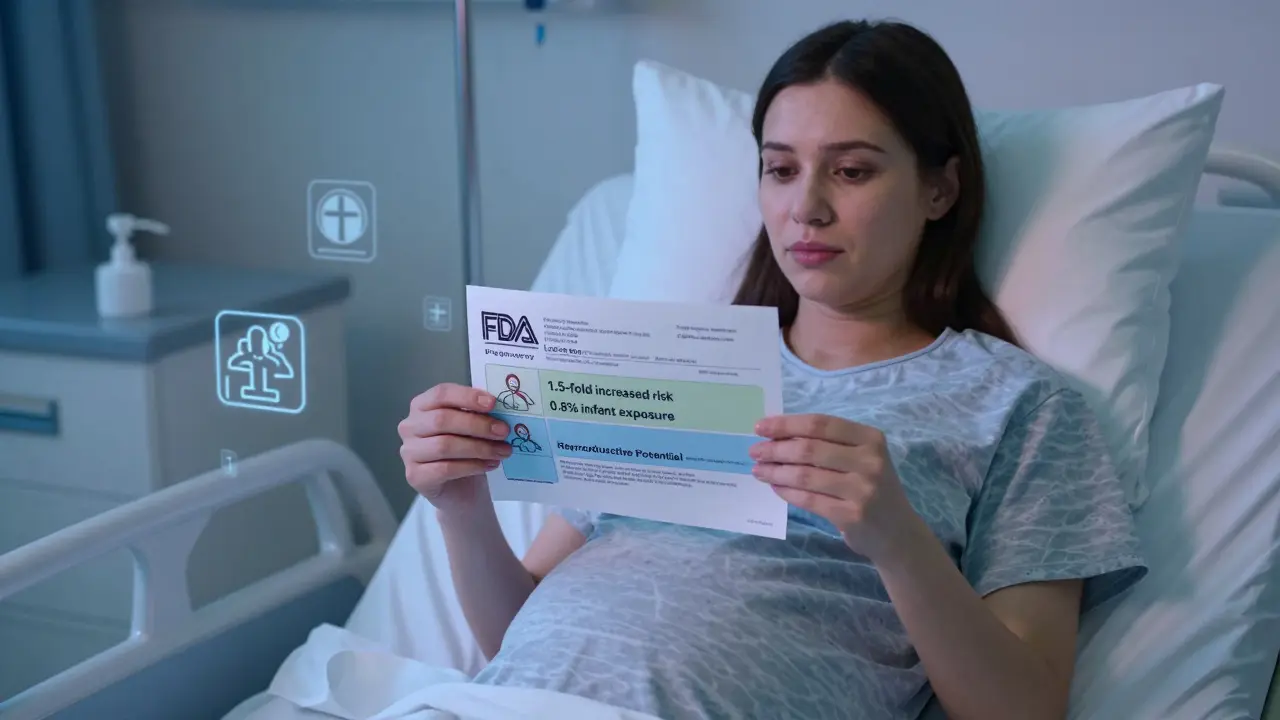

- “Exposure during the first trimester was associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk of neural tube defects.”

- “No increase in risk was observed in 1,200 prospectively followed pregnancies.”

- When to avoid the drug (e.g., “Avoid use after 20 weeks due to risk of fetal kidney damage”)

- What monitoring is needed (e.g., “Fetal echocardiogram recommended at 22 weeks”)

- When to adjust dosage (e.g., “Increase dose in third trimester due to increased clearance”)

Understanding Lactation Labeling (8.2)

Breastfeeding mothers face a different question: How much of this drug gets into my milk? And will it affect my baby? The Lactation section answers this with specific numbers. Look for phrases like:- “Infant exposure is estimated at 0.8% of the maternal weight-adjusted dose.”

- “Milk-to-plasma ratio is 0.3, indicating low transfer.”

- “No adverse effects reported in 120 breastfed infants followed for 6 months.”

What About Fertility and Contraception? (8.3)

This section often gets overlooked, but it’s critical for women planning pregnancy or using contraception. It tells you:- Whether the drug affects fertility (e.g., “Reversible reduction in sperm count observed in 15% of men after 6 months of use”)

- When to stop taking it before trying to conceive (e.g., “Discontinue 3 months prior to conception due to long half-life”)

- What contraceptive methods are recommended and their failure rates (e.g., “Use of combined hormonal contraceptives not recommended due to increased thrombotic risk; suggest IUD with <1% failure rate”)

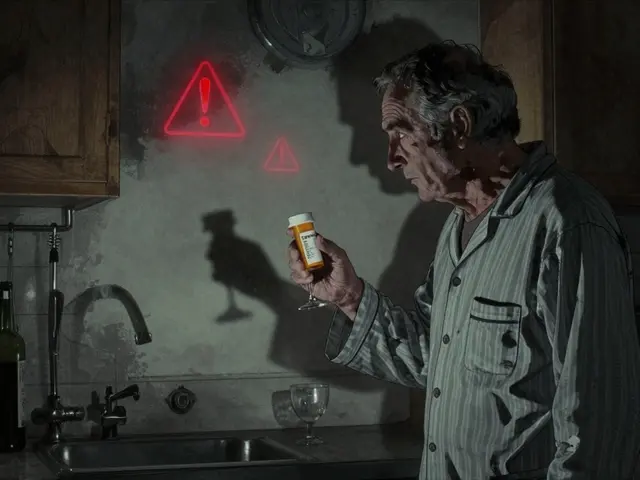

Why the Old System Failed

The old letter system was broken because it treated risk like a grade on a test. A “B” sounded safe. A “D” sounded scary. But a “C” drug could be a life-saving epilepsy medication-or a harmless antihistamine. The system didn’t help you weigh benefits against risks. A 2018 study found that 62% of obstetricians struggled to interpret the new PLLR labels at first. Why? Because they were used to quick answers. But the real world isn’t simple. A drug might be safe in the second trimester but risky in the first. It might be safe for the baby but dangerous for the mother’s mental health. The new system forces you to think about trade-offs. The FDA’s own data shows the new labels cut misinterpretation in half-from 68% to 31%. That’s a win. But it comes with a cost: more time. Pharmacists now spend 5-7 extra minutes per prescription counseling. Clinicians report needing 3-5 label reviews before feeling confident.

What Should You Do When You See a New Label?

Here’s a simple step-by-step approach:- Start with the Risk Summary. What’s the background risk? What’s the increase? Is the increase statistically significant?

- Check the timing. Is the risk limited to the first trimester? The third? Or does it apply throughout?

- Look at the Clinical Considerations. Are there monitoring steps? Dosage adjustments? Alternatives?

- Review the Lactation section. If you’re breastfeeding, what’s the infant exposure? Are there documented effects?

- Read the Data. How big was the study? Was it observational or controlled? Are there limitations?

Real-World Impact

Since the PLLR launched, participation in pregnancy exposure registries has jumped from 5,000 pregnancies per year to over 25,000. That’s because the labeling now requires manufacturers to list active registries. More data means better science. A 2022 survey found 73% of perinatal specialists prefer the narrative format for complex cases. Why? Because it lets them say: “This drug increases risk from 2% to 3%, but stopping it could cause a seizure that harms both you and your baby.” That’s a real conversation. The old system couldn’t do that. Still, gaps remain. A 2023 report found that 63% of psychiatric drug labels don’t specify which trimester carries the highest risk-even though timing matters. And only 15% of registry participants are Black or Hispanic, even though they make up 30% of U.S. pregnancies. That’s a problem researchers are working to fix.Final Takeaway

The FDA’s new drug labeling isn’t perfect-but it’s the best system we’ve ever had. It replaces guesswork with facts. It turns vague warnings into measurable risks. It gives you the tools to make informed choices, not just avoid drugs out of fear. If you’re pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to be, don’t skip reading the label. Ask your provider: “Can you walk me through the Risk Summary and Clinical Considerations?” You’re not just asking for safety-you’re asking for clarity. And that’s worth the extra few minutes.Are the old pregnancy letter categories still used on drug labels?

No. As of December 2020, all prescription drug labels in the U.S. must use the new PLLR format. Any remaining labels with A, B, C, D, or X categories are outdated and should be replaced. Manufacturers were required to update all existing products by that date, though some older stock may still be in circulation. Always check the FDA-approved labeling on the manufacturer’s website or through the FDA’s Drug Labeling database.

What does "infant exposure of 0.5% of maternal dose" mean?

It means that for every 100 milligrams of the drug you take, your baby receives about 0.5 milligrams through breast milk. This is considered very low exposure. Most drugs with infant exposure under 1% are considered compatible with breastfeeding. For context, a typical infant receives 10-20% of their body weight in milk daily, so even low percentages can add up-but at 0.5%, the amount is usually too small to cause effects.

Can I trust the "Data" section if it’s based on observational studies?

Yes-but with context. Most pregnancy data comes from observational studies because you can’t ethically randomize pregnant women to take or avoid a drug. These studies track women who chose to take the medication and compare outcomes to those who didn’t. While not as strong as randomized trials, they’re still valuable, especially when they’re large, prospective, and control for confounding factors like smoking or age. Look for phrases like “adjusted odds ratio” or “controlled for maternal age and BMI”-these indicate better quality.

What if the label says "no data available"?

That means there are no published human studies on the drug’s use during pregnancy or lactation. It doesn’t mean the drug is dangerous-it just means no one has studied it yet. In these cases, experts rely on animal data, pharmacokinetics (how the drug moves in the body), and similar drugs. Talk to a specialist or contact MotherToBaby for personalized advice. Never assume “no data” means “not safe.”

Do over-the-counter (OTC) drugs have PLLR labeling?

No. The PLLR applies only to prescription drugs. OTC medications still use simplified language like “consult your doctor if pregnant” or “not recommended during breastfeeding.” Some OTC drugs may have more detailed information on their websites, but there’s no federal requirement. Always check with a pharmacist or provider before using OTC drugs during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Where can I find the official PLLR label for a specific drug?

Go to the FDA’s Drugs@FDA database (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/) and search by drug name. Look for the "Label" section and download the most recent version. You can also check the manufacturer’s website-most now include the full PLLR-compliant labeling in their product information. Avoid relying on third-party sites like WebMD or Medscape for full details; they may not reflect the latest FDA-mandated format.

If you’re managing a chronic condition like epilepsy, depression, or hypertension during pregnancy, the PLLR labels are your most reliable tool. They don’t give easy answers-but they give you the truth. And that’s what matters most.

Alec Stewart Stewart

4 February 2026 - 12:17 PM

Finally! I’ve been trying to explain this to my sister who’s pregnant and on antidepressants. The old A-B-C-D-X system was useless. Now I can actually show her: 'Hey, your med has a 1.5x increase, but baseline is 2% - so it’s still under 3%. That’s like rolling a dice and getting a 3 instead of a 2.' 😌

Demetria Morris

6 February 2026 - 03:21 AM

It’s irresponsible to think patients can interpret clinical data on their own. This ‘transparency’ is just exposing vulnerable people to terrifying statistics without context. Who’s going to explain CI intervals to a 24-year-old who just found out she’s pregnant? This isn’t empowerment - it’s emotional neglect.

Susheel Sharma

6 February 2026 - 22:08 PM

The FDA’s new system is a masterclass in bureaucratic overengineering. 70% of drugs were Category C? So now we have three subsections, each with three sub-subsections, and a 47-page appendix on ‘data transparency.’ Meanwhile, real doctors still say ‘it’s probably fine’ and move on. All this for a 0.7% improvement in decision-making. 🤡

Janice Williams

7 February 2026 - 20:31 PM

This is yet another example of how medicine has abandoned moral clarity in favor of statistical ambiguity. When a drug carries any risk, it should be labeled as such - plainly, unequivocally. The new system allows pharmaceutical companies to bury danger under numbers. If a drug causes neural tube defects, it should say: 'DO NOT USE IN PREGNANCY.' Not '1.5-fold increase.' That’s not transparency - that’s obfuscation.

Roshan Gudhe

7 February 2026 - 21:37 PM

I’ve been thinking about this as a philosophical shift. The old system treated pregnancy like a binary state: safe or dangerous. But life isn’t binary. Risk is a spectrum. The new system acknowledges that. A 2% baseline risk isn’t ‘safe’ - it’s just normal human biology. The drug nudges it to 3%. That’s not a catastrophe. It’s a whisper. And we’re finally learning to listen to whispers instead of shouting at shadows.

Rachel Kipps

9 February 2026 - 11:40 AM

Just read the lactation section on sertraline - the milk-to-plasma ratio is 0.3? That’s so helpful. I’m breastfeeding my third and finally feel like I’m not guessing anymore. The data says ‘no adverse effects in 120 infants’ - that means something. Thank you, FDA. 😊

Alex LaVey

11 February 2026 - 05:50 AM

As someone who’s been on blood pressure meds through two pregnancies, I can’t tell you how much this means. I used to panic every time I had to refill a prescription. Now I can look at the label and say, ‘Okay, my dose goes up in the third trimester because my body’s clearing it faster.’ That’s not just information - that’s peace of mind. 🙏

Jhoantan Moreira

12 February 2026 - 00:13 AM

Love this. Finally, something that treats patients like adults. I’m from the UK, and our system still uses the old letters. Seeing this change in the US gives me hope. Maybe one day, we’ll stop talking in code and start talking in science. 🌍💙

Justin Fauth

12 February 2026 - 02:21 AM

They took away the letters? Are you kidding me? Back in my day, if it was a C, you didn’t take it. Period. Now you’ve got moms scrolling through CI intervals like they’re reading stock charts. This isn’t progress - it’s chaos. And don’t get me started on the ‘fertility’ section - who’s got time for this? We got babies to make, not spreadsheets!

Meenal Khurana

12 February 2026 - 10:36 AM

Good change. Clearer data. More trust.

Zachary French

13 February 2026 - 03:54 AM

Let’s be real: this is just Big Pharma’s PR play dressed up as science. They knew the old system was collapsing under its own stupidity, so they created a 3000-word wall of text that sounds impressive but still doesn’t tell you if your baby will be fine. The data section? 120 infants? That’s a drop in the ocean. Where’s the 10-year follow-up? The autism correlation? The epigenetic studies? This isn’t transparency - it’s theater. 🎭

Mandy Vodak-Marotta

13 February 2026 - 11:01 AM

Okay, so I’m a nurse and I’ve been reading these new labels for a year now. Honestly? It’s been a game-changer. I had a patient last month who was terrified of her anxiety med because it was ‘Category C.’ I pulled up the label, showed her the risk summary - baseline 2%, drug adds 0.5%, so 2.5% total. Then I showed her the lactation data: 0.7% of maternal dose. She cried. Not from fear - from relief. She said, ‘I didn’t know I could still breastfeed.’ And now she’s doing it. So yeah, this isn’t just paperwork. It’s life-changing. I wish every drug label looked like this. Seriously. 😭