When you slam a weight, sprint off a sudden sprint, or take a hard fall, the muscles around the affected area can go into crisis within minutes. These emergencies-collectively known as Acute skeletal muscle conditions are a group of injuries that develop quickly, cause sharp pain, and often need immediate care to prevent long‑term disability.

Key Takeaways

- Muscle strains, tears, contusions, compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis and acute myositis cover the most frequent acute muscle problems.

- Early diagnosis and condition‑specific treatment-RICE, NSAIDs, surgery or fasciotomy-dramatically improve outcomes.

- Lab values (CK > 5,000U/L for rhabdomyolysis) and neurovascular checks are essential red‑flag tools.

- Rehabilitation should progress from protected motion to strength, with a clear return‑to‑activity timeline.

- Prevention hinges on proper warm‑up, load management and early treatment of minor symptoms.

What Counts as an Acute Skeletal Muscle Condition?

These injuries arise suddenly, often during sports, manual labor, or accidental trauma. Unlike chronic tendinopathies that develop over months, acute conditions demand a rapid response because the tissue damage can worsen within the first 24‑48hours. The most common culprits are:

- Muscle strain

- Muscle tear (complete rupture)

- Muscle contusion (bruise)

- Acute compartment syndrome

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Acute myositis

Understanding each entity’s anatomy, typical mechanism, and hallmark signs guides the right treatment plan.

1. Muscle Strain - The Most Frequent Twinge

Muscle strain is a stretch‑induced injury of muscle fibers or the surrounding tendinous attachment. Strains are graded by severity:

- GradeI: Microscopic fiber tears, mild pain, full range of motion (ROM).

- GradeII: Partial fiber rupture, moderate pain, limited ROM, possible swelling.

- GradeIII: Complete rupture, severe pain, loss of function, palpable defect.

Typical zones are the hamstrings, gastrocnemius, and quadriceps-muscles that undergo rapid eccentric loading. Early signs include a sudden “pop” sensation and localized tenderness.

First‑line Management

- Apply RICE (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) for 48‑72hours.

- NSAIDs such as ibuprofen (400mg every 6h) reduce inflammation, unless contraindicated.

- Begin gentle passive stretching after pain subsides (usually day3).

- Progress to isometric strengthening (e.g., static quad holds) around day5‑7.

If a GradeIII injury is suspected, MRI confirms fiber discontinuity and surgical repair may be needed within 2weeks to restore optimal length‑tension.

2. Muscle Tear - When the Fibers Give Way

Muscle tear denotes a full‑thickness rupture of a muscle belly or its tendon. Common sites are the biceps brachii, pectoralis major, and calf muscles. Patients report a violent tearing feeling, rapid swelling, and inability to contract the affected muscle.

Diagnostic Clues

- Visible contour defect or palpable gap.

- Ultrasound shows anechoic gap; MRI displays fluid‑filled cavity.

- Functional loss: inability to plantarflex the ankle with a gastrocnemius tear.

Treatment Options

- Immediate immobilization in a functional brace (e.g., hinged knee brace for quadriceps tear).

- Analgesic and anti‑inflammatory regimen (acetaminophen+naproxen).

- Early physiotherapy focusing on controlled passive motion (day3‑5) to prevent adhesions.

- Surgical repair when the gap exceeds 2cm or for elite athletes; primary end‑to‑end suture with reinforced epitendinous stitches.

- Post‑op protocol: protected weight‑bearing for 2weeks, then progressive resistance training over 8‑12weeks.

3. Muscle Contusion - The Hidden Bruise

Muscle contusion is a blunt‑force injury that crushes muscle tissue and ruptures capillaries, leading to a bruise and swelling. Soccer tackles and falls from height are typical causes. The hallmark is localized pain, ecchymosis, and a tight, swollen muscle belly.

When to Worry

If compartment pressure spikes (see compartment syndrome below) or if there is progressive numbness, the contusion may be evolving into a more serious condition.

Standard Care

- Ice for 20minutes every 2hours during the first 24hours.

- Compression bandage to limit edema.

- Analgesics (acetaminophen) rather than NSAIDs if bleeding risk exists.

- Gentle ROM exercises after 48hours; avoid heavy loading for 1‑2weeks.

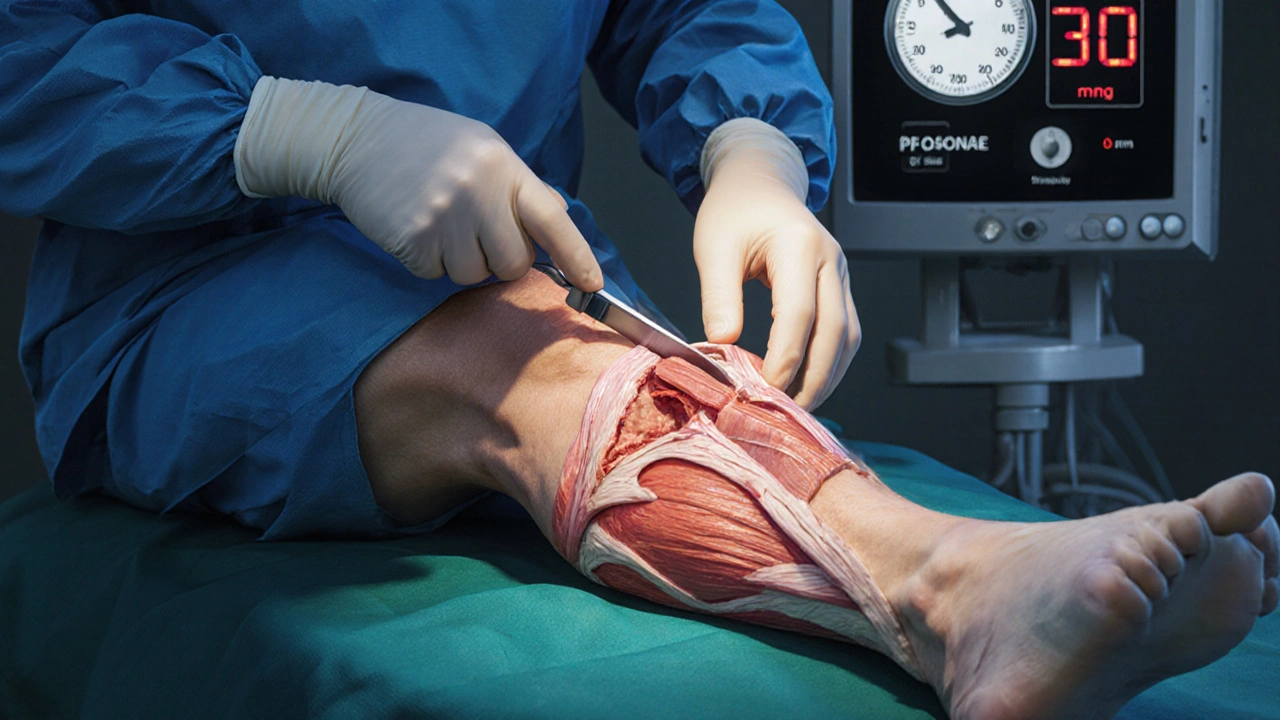

4. Acute Compartment Syndrome - A Surgical Emergency

Acute compartment syndrome occurs when increased pressure within a closed osteofascial compartment compromises blood flow and nerve function. It most often follows tibial fractures, severe contusions, or high‑intensity exercise with prolonged muscle compression (e.g., rock climbing). The classic “6P’s” (Pain, Paresthesia, Pallor, Pulselessness, Paralysis, Poikilothermia) signal impending tissue death.

Measuring Pressure

Needle manometry reading >30mmHg (or delta pressure <20mmHg) confirms diagnosis. Bedside devices are now handheld and give rapid results.

Definitive Treatment

- Immediate removal of any constrictive dressings or casts.

- Analgesia and fluid resuscitation to maintain perfusion.

- Urgent fasciotomy (surgical release of the fascia) performed within 6hours of diagnosis reduces the risk of permanent contracture to <10%.

- Post‑operative wound management: delayed primary closure after 48‑72hours, followed by gradual mobilization.

Delay beyond 12hours spikes the amputation‑rate to 30% and significantly worsens functional outcomes.

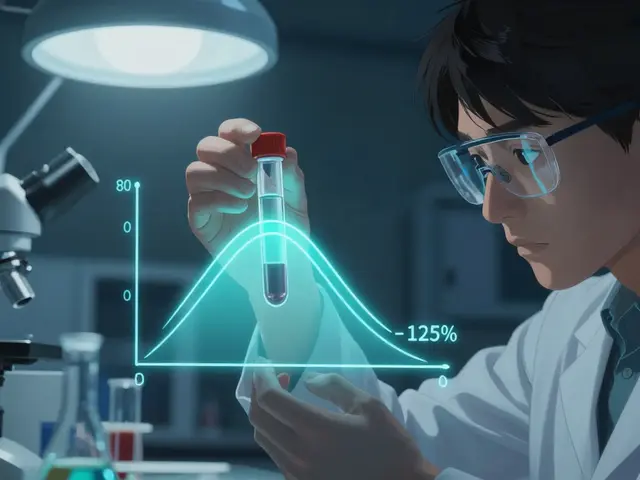

5. Rhabdomyolysis - When Muscle Breaks Down Systemically

Rhabdomyolysis is the rapid necrosis of skeletal muscle fibers, releasing myoglobin, creatine kinase (CK), and electrolytes into the bloodstream. Common triggers include extreme exertion (marathons, CrossFit), crush injuries, and certain drugs (statins, cocaine).

Red‑Flag Laboratory Values

- CK >5,000U/L (often >20,000U/L in severe cases).

- Urine dark‑brown, positive for heme on dipstick but no RBCs on microscopy (myoglobinuria).

- Hyperkalemia (>5.5mmol/L) and metabolic acidosis.

Life‑Saving Management

- Aggressive IV hydration (alkaline saline, 250‑500mL/hour) to maintain urine output >200mL/hour.

- Alkalinization with sodium bicarbonate (if urine pH <6.5) to reduce tubular injury.

- Monitor electrolytes every 4‑6hours; treat hyperkalemia with calcium gluconate, insulin‑glucose, or dialysis if needed.

- Consider renal replacement therapy if creatinine rises >2mg/dL or oliguria persists >24hours.

Most patients recover full muscle function within 4‑6weeks if the kidneys are spared.

6. Acute Myositis - Inflammation That Hits Fast

Acute myositis is an inflammatory infiltration of skeletal muscle, often viral (influenza, COVID‑19) or bacterial (Staphylococcus aureus) in origin. Symptoms include diffuse muscle tenderness, fever, and mild CK elevation (typically 200‑800U/L).

Diagnostic Approach

- History of recent infection or immunization.

- Elevated inflammatory markers (CRP>10mg/L, ESR>30mm/hr).

- MRI shows diffuse T2 hyperintensity without focal rupture.

Treatment Pathway

- Address the underlying pathogen: antiviral (oseltamivir for flu) or appropriate antibiotics.

- Short course of corticosteroids (prednisone 0.5mg/kg for 5days) for severe pain.

- Analgesic regimen: acetaminophen + tramadol if needed.

- Gradual re‑introduction of activity once fever resolves and pain drops below 3/10.

Comparison Table: Conditions vs First‑Line Treatment

| Condition | Typical Onset | Key Diagnostic Cue | First‑Line Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle strain | Seconds‑minutes | Sudden “pop”, localized tenderness | RICE + NSAIDs, progressive rehab |

| Muscle tear | Immediate | Palpable gap, loss of function | Immobilization, surgical repair for >2cm |

| Muscle contusion | Instant | Bruising, swelling, tender lump | Ice, compression, limited loading |

| Compartment syndrome | Hours after trauma | Pressure ≥30mmHg, 6P’s | Urgent fasciotomy |

| Rhabdomyolysis | Hours‑days | CK >5,000U/L, dark urine | IV fluids, electrolyte management |

| Acute myositis | Days after infection | Fever + mild CK rise, MRI T2 signal | Treat underlying pathogen + short steroids |

Rehabilitation Roadmap - From Pain to Performance

Regardless of the exact injury, a structured rehab plan accelerates healing and reduces re‑injury risk.

- Phase1 (0‑3days): Protect tissue, control pain, maintain joint ROM.

- Gentle pendulum swings for shoulder injuries.

- Passive ankle pumps for calf contusions.

- Phase2 (4‑14days): Begin light isometric contractions and neuromuscular activation.

- Quadriceps sets, gluteal bridges.

- Progress to active‑assisted ROM when swelling subsides.

- Phase3 (2‑6weeks): Load‑bearing exercises, eccentric training for strains, and functional drills.

- Step‑down lunges for hamstring strains.

- Band‑resisted hip abduction for post‑contusion stability.

- Phase4 (6‑12weeks): Sport‑specific power and agility work.

- Box jumps, ladder drills, and progressive sprint intervals.

- Re‑evaluate with functional testing (e.g., hop test for lower‑extremity injuries).

For compartment syndrome and rhabdomyolysis, clearance from a physician is mandatory before entering Phase2.

Prevention Tips - Keep Muscles Ready

- Dynamic warm‑up (leg swings, arm circles) for ≥10minutes before activity.

- Gradual progression of load; avoid >10% weekly increase in training volume.

- Hydration and electrolyte balance, especially in hot environments, to lower rhabdomyolysis risk.

- Strengthen opposing muscle groups (e.g., hamstrings vs quadriceps) to maintain balanced forces.

- Use protective gear (shin guards, padding) during contact sports.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell the difference between a muscle strain and a tear?

A strain usually feels like a mild pull and retains most strength; a tear presents with a noticeable gap, dramatic loss of power, and often a bulge in the muscle. Imaging (ultrasound or MRI) confirms the extent.

When is compartment syndrome a surgical emergency?

If the compartment pressure exceeds 30mmHg (or the delta pressure-diastolic BP minus compartment pressure-is less than 20mmHg) and the patient has progressive pain or neurovascular signs, immediate fasciotomy is required.

What urine color indicates possible rhabdomyolysis?

Dark tea‑ or cola‑colored urine, often described as “brown,” signals myoglobin release. A dipstick will read positive for blood despite a lack of red cells on microscopy.

Can I treat a mild muscle contusion at home?

Yes. Ice, compression, elevation, and avoiding heavy loading for 1‑2weeks usually resolve a GradeI‑II contusion. Seek medical care if swelling worsens or you notice numbness.

How long should I wait before returning to sports after a GradeII strain?

Most athletes resume sport between 3‑6weeks, provided they have pain‑free full ROM, can perform eccentric loading without discomfort, and pass a functional hop test.

Next Steps if You Suspect an Acute Muscle Issue

If pain, swelling, or functional loss appears suddenly, follow this quick checklist:

- Stop the activity and assess for a visible defect or severe pain.

- Apply ice and compression; elevate the limb.

- Check neurovascular status (pulses, sensation).

- Measure compartment pressure if you suspect compartment syndrome (many urgent‑care centers have handheld kits).

- Obtain lab work (CK, electrolytes, renal function) when rhabdomyolysis is possible.

- Seek medical evaluation-ER for compartment syndrome, urgent clinic for suspected tear or severe strain, primary‑care for contusion or myositis.

Timely actions keep you from a long rehab or permanent loss of function.

Trinity 13

5 October 2025 - 01:43 AM

When you think about tearing a muscle you’re really looking at a tiny battle between fibers that can quickly become a saga of pain and recovery. It’s not just a pop or a twinge; it’s the body shouting that you’ve crossed a threshold you didn’t even know existed. The first thing to remember is that every injury carries a lesson about load management and respect for your own limits. You can’t outrun the physics of eccentric overload, and the instant you do, you’re inviting inflammation to set up camp. Apply the classic RICE protocol, but treat it like a ritual – rest the damaged tissue, ice it like you’re cooling a hot engine, compress it with purpose, and elevate it to keep blood from pooling. While the swelling subsides, keep the surrounding joints moving; you don’t want the whole limb to go into hibernation. Pain is your compass, not an invader, so listen to it and adjust intensity accordingly. As the first week passes, shift from passive stretches to gentle isometrics; think of them as the scaffolding that will later support full strength. When you get to day five, introduce light eccentric work – slow, controlled lengthening that teaches the fibers to absorb stretch without breaking. Nutrition matters too; protein and anti‑oxidants act like repair crews arriving on schedule. Hydration is the oil that keeps every cellular process humming, especially when you’re fighting off myoglobin spill in rhabdomyolysis‑prone scenarios. If you ever suspect a full‑thickness tear, don’t gamble with self‑diagnosis – get an MRI or at least an ultrasound before you think about surgery. In the meantime, brace the area, but don’t let it become a permanent crutch; you need the safe stress to guide remodeling. Rehabilitation isn’t a straight line; expect setbacks, but each one is a data point that refines your next move. Keep a journal of pain levels, ROM, and strength gains – that record will become your roadmap back to sport. Finally, remember that prevention is far cheaper than cure: dynamic warm‑ups, gradual load increases, and consistent mobility work keep the 6Ps of compartment syndrome at bay. So, treat every strain as a chapter in your personal textbook on resilience, and you’ll emerge not just healed, but wiser.

faith long

10 October 2025 - 20:36 PM

I feel your frustration when a seemingly minor pull spirals into a full‑blown tear, and it’s infuriating that the medical system sometimes downplays the seriousness. You’ve done the right thing by ice‑ing early, but now the swelling isn’t shrinking, which screams that deeper damage may be lurking. Keep the limb elevated and start gentle passive motion, but don’t wait for pain to vanish before seeking imaging – a missed diagnosis can cost months of rehab. If you notice dark urine or a sudden spike in fatigue, that’s a red flag for rhabdomyolysis, and you need IV fluids yesterday. Stay vigilant, trust your body’s signals, and push for the proper work‑up now.

Adam Khan

16 October 2025 - 15:29 PM

From a biomechanical standpoint, the acute strain you described exhibits a classic type II fiber failure under eccentric overload, resulting in a localized inflammatory cascade mediated by cytokines such as IL‑6 and TNF‑α. Immediate application of cryotherapy attenuates the nociceptive afferents by vasoconstriction, thereby limiting secondary hyperemia. Subsequent progression to isometric contractions at 30% MVC facilitates sarcomere realignment while preserving the extracellular matrix integrity. In cases where the disruption exceeds 2 cm, surgical intervention via end‑to‑end suture with epitendinous reinforcement is indicated to restore optimal tensile strength. Finally, serial CK monitoring provides quantitative insight into myocyte necrosis, guiding hydration protocols to preempt acute kidney injury.

rishabh ostwal

22 October 2025 - 10:23 AM

While your holistic narration captures the emotional arc of healing, I must caution that the dramatization of “battle” can mislead lay readers into underestimating the clinical urgency of compartment syndrome. The six P’s, especially pulselessness, demand immediate fasciotomy rather than a prolonged “ritual.” Therefore, any instructional piece should prioritize unequivocal red‑flag criteria over metaphorical language.

Kristen Woods

28 October 2025 - 04:16 AM

i t's tru that medical folk can be alwyas to slow at watch outs, but you cant just wait for a scan. you must push for an mri asap.

Carlos A Colón

2 November 2025 - 23:09 PM

Oh sure, just chill and watch your muscle melt away.

Aurora Morealis

8 November 2025 - 18:03 PM

Ice early compression later keep moving. Simple.

Sara Blanchard

14 November 2025 - 12:56 PM

That's a solid starter, but remember to add gentle ROM after the first 48 hours to keep joints from stiffening. Everyone benefits from that extra movement, especially if they're returning to sport quickly.

Anthony Palmowski

20 November 2025 - 07:49 AM

Wow!!! You really threw a lot of fancy terms at us!!! But hey, if you can actually explain what “MVC” means to a regular gym‑goer, maybe they'd finally understand why those isometric holds matter!!!

Jillian Rooney

26 November 2025 - 02:43 AM

i guess some people think a bruise is just a fashion statement, but when it hurts you should probably see a doc lol.

Rex Peterson

1 December 2025 - 21:36 PM

Indeed, the phenomenology of pain transcends mere aesthetic interpretation; it is an epistemic signal that obliges the subject to re‑evaluate the somatic ontology of the affected limb. Hence, a prudent clinician must heed this manifestation with both empirical rigor and ontological humility.

Candace Jones

7 December 2025 - 16:29 PM

When you’re dealing with a Grade‑II strain, aim for a pain‑free full range of motion before introducing eccentric loading. A gradual progression reduces the risk of re‑injury and sets a solid foundation for a safe return to sport. Consistency in your rehab schedule is key; even short daily sessions outperform sporadic intense workouts.

Robert Ortega

13 December 2025 - 11:23 AM

That's a good point, consistency often beats intensity in the long run.

Elizabeth Nisbet

19 December 2025 - 06:16 AM

Yo, if you’ve got a contusion, ice it like crazy for the first day, then start moving that joint gently. Don’t skip the compression bandage – it’ll keep the swelling down and you’ll be back faster.

Sydney Tammarine

25 December 2025 - 01:09 AM

Honestly, a bruise is just a dramatic reminder that your body isn’t a rubber band 😏. Treat it with care or it’ll keep reminding you.

josue rosa

30 December 2025 - 20:03 PM

Addressing acute muscle injuries requires a multidisciplinary mindset that integrates pathophysiology, early intervention protocols, and progressive rehabilitation strategies. First, accurate classification-whether strain, tear, contusion, or compartment syndrome-guides the therapeutic algorithm. Immediate measures such as RICE and NSAID administration mitigate inflammatory mediators, yet they must be paired with vigilant neurovascular monitoring to detect evolving complications. For suspected compartment syndrome, continuous pressure monitoring and rapid surgical fasciotomy are non‑negotiable to preserve limb viability. In cases of rhabdomyolysis, aggressive isotonic fluid resuscitation with urine output targets above 200 ml/h forestalls renal injury. Throughout the rehab continuum, emphasis on controlled mobilization, proprioceptive training, and graded loading fosters functional recovery while minimizing scar tissue formation. Finally, patient education on load management, warm‑up routines, and early symptom reporting creates a preventative framework that reduces recurrence. By adhering to these evidence‑based pillars, clinicians can optimize outcomes and expedite the athlete’s return to competition.

Angie Wallace

5 January 2026 - 14:56 PM

All solid steps. Just remember to stay hydrated.

Doris Montgomery

11 January 2026 - 09:49 AM

The article is thorough but feels like a textbook read.

Nick Gulliver

17 January 2026 - 04:43 AM

Well, if you’re not willing to dive deep, you’re missing the real American spirit of hard work and toughness.

Sadie Viner

22 January 2026 - 23:36 PM

In summarizing the management of acute skeletal muscle conditions, it is essential to align diagnostic vigilance with timely therapeutic action. Early identification of red‑flag signs-such as the 6 P’s of compartment syndrome or a CK exceeding 5,000 U/L-should precipitate immediate intervention, whether that be emergency fasciotomy or aggressive IV hydration. Tailoring the rehabilitation phases to the specific pathology ensures progressive loading without jeopardizing tissue integrity. Moreover, incorporating preventive strategies like dynamic warm‑ups, graduated load increments, and adequate hydration serves to mitigate future incidents. By integrating these evidence‑based practices, clinicians and athletes alike can navigate the delicate balance between swift recovery and sustained performance.