Antimalarial QT Risk Calculator

This tool assesses your risk of QT prolongation when taking antimalarial drugs with other medications. Based on clinical evidence, certain combinations can significantly increase your risk of dangerous heart rhythms. Always consult your healthcare provider before making any changes to your medications.

When you take an antimalarial drug, you’re not just fighting malaria-you’re also risking your heart. That’s not fearmongering. It’s science. Drugs like hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and lumefantrine can stretch out your heart’s electrical cycle, leading to a dangerous rhythm called Torsades de Pointes. And if you’re on other medications-common ones like antibiotics or heart pills-that risk spikes dramatically. This isn’t rare. It’s happening in clinics, hospitals, and travel clinics every day.

How Antimalarials Mess With Your Heart’s Electrical System

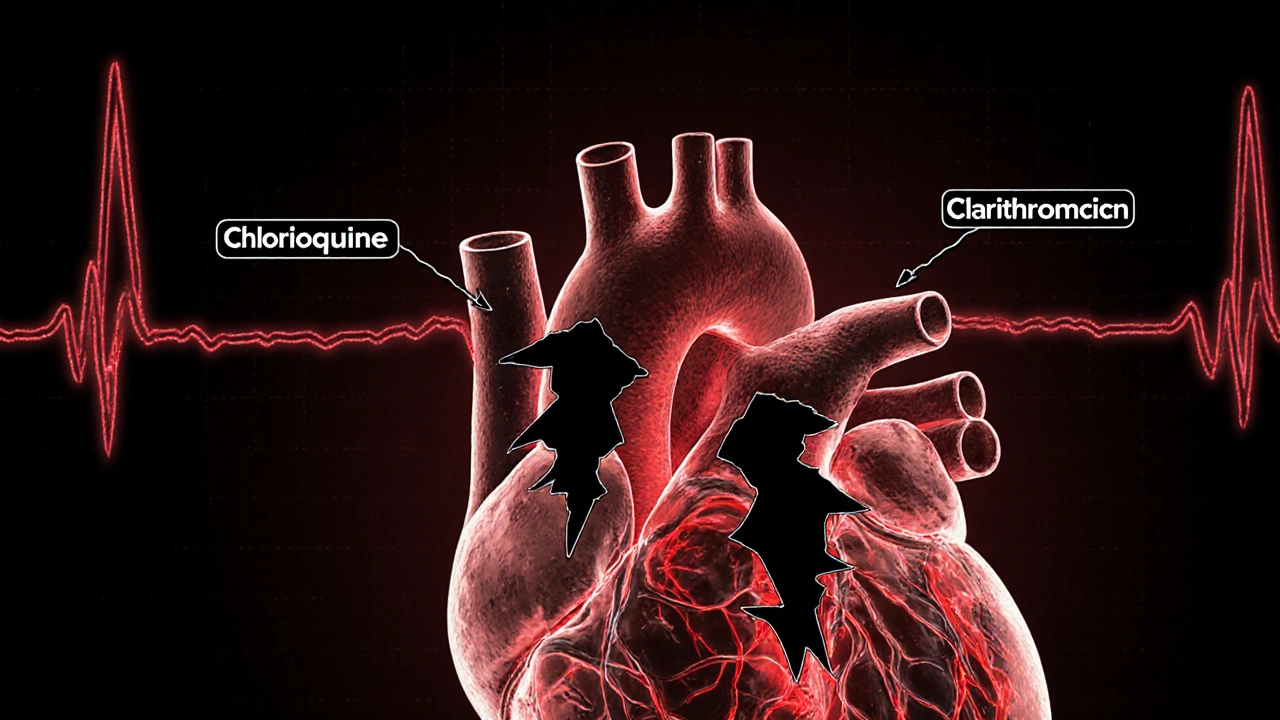

Antimalarials don’t just kill parasites. They also block ion channels in heart cells, especially the hERG channel that controls potassium flow. When that channel gets blocked, the heart takes longer to reset after each beat. That delay shows up on an ECG as a prolonged QT interval. When QT goes beyond 500 milliseconds-or increases more than 60 ms from baseline-it’s a red flag.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are the worst offenders. They don’t just hit hERG. They also block calcium and ATP-sensitive potassium channels. That’s a triple threat. Mefloquine does something similar, with studies showing it blocks hERG at concentrations as low as 10 micromolar. Even artemether, often seen as safer, has a quiet danger: it can make other drugs stick around longer in your body by messing with liver enzymes.

Here’s the catch: you won’t feel it coming. No chest pain. No dizziness. Just a silent delay in your heartbeat that can spiral into sudden cardiac arrest. That’s why monitoring isn’t optional-it’s life-saving.

CYP Enzymes: The Hidden Drug Traffic Controllers

Your liver uses enzymes called cytochrome P450 (CYP) to break down drugs. Think of them as toll booths on a highway. Some antimalarials are cargo trucks that need to pass through. Others are roadblocks that slow everything down. The biggest player here is CYP3A4.

Artemether turns into dihydroartemisinin (DHA) via CYP3A4. If you’re taking something that blocks CYP3A4-like clarithromycin, ketoconazole, or even some HIV meds-your body can’t convert artemether properly. That means less active drug in your system. But here’s the twist: artemether itself still works. So the real danger isn’t treatment failure-it’s the buildup of lumefantrine, its partner drug. Lumefantrine has a half-life of 3 to 6 days. It lingers. And it’s a known QT prolonger.

Hydroxychloroquine is metabolized by CYP2C8, CYP3A4, and CYP2D6. That means it can clash with a wide range of meds: statins, antidepressants, beta-blockers. The worst offender? Clarithromycin. A 2021 study found patients on both drugs had an 17.85 times higher chance of QT prolongation. That’s not a small bump. That’s a cliff.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

This isn’t just about the drugs. It’s about the person taking them.

- Older adults-especially over 65-have slower liver and kidney function. Lipophilic drugs like hydroxychloroquine build up in fat tissue and stick around for weeks. Half-life? 40 to 50 days. That’s not a short-term fix. That’s a long-term hazard.

- People with heart disease-even mild arrhythmias or prior heart attacks-can’t handle extra stress on the QT interval.

- Those on multiple QT-prolonging drugs-like fluoxetine, amiodarone, or even some antifungals. Each one adds a layer of risk.

- Patients on HIV treatment-protease inhibitors like ritonavir are strong CYP3A4 inhibitors. Combining them with artemether-lumefantrine? Not recommended without close monitoring.

- Women-on average, women have longer baseline QT intervals than men. That small difference becomes dangerous when drugs pile up.

And it’s not just travelers. Hydroxychloroquine is prescribed for lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. There are an estimated 1.5 million Americans on it. Many don’t even know they’re at risk for cardiac side effects because they’re not taking it for malaria.

Drugs That Should Never Mix

A 2021 study by Choi et al. identified 12 drugs that, when paired with hydroxychloroquine, significantly increase QT prolongation risk. Here are the top three:

- Clarithromycin-OR 17.85. This antibiotic is a major CYP3A4 blocker. Avoid entirely.

- Piperacillin/tazobactam-a common IV antibiotic. Even though it’s not known for QT issues on its own, it becomes dangerous with hydroxychloroquine.

- Furosemide-a diuretic. Low potassium from furosemide makes QT prolongation worse. It’s a double whammy.

Other high-risk combos:

- Lumefantrine + fluconazole (antifungal)

- Chloroquine + ciprofloxacin (antibiotic)

- Artemether-lumefantrine + ritonavir (HIV drug)

Even azithromycin, often called “safe,” has been linked to TdP cases. Don’t assume safety. Check every single med.

What You Need to Do Before Prescribing or Taking

There’s no magic bullet. But there’s a clear checklist:

- Review all medications-prescription, OTC, supplements. Even St. John’s wort can induce CYP3A4 and reduce artemether’s effect.

- Get a baseline ECG-before starting any high-risk antimalarial. Measure QTc. Record it.

- Check electrolytes-low potassium or magnesium makes QT prolongation more likely. Fix them first.

- Know the half-lives-hydroxychloroquine stays for weeks. Mefloquine for months. Don’t assume it’s gone after you stop.

- Monitor during treatment-repeat ECG after 5-7 days if on hydroxychloroquine or lumefantrine. Especially if you’re on a new drug.

- Use alternatives when possible-atovaquone-proguanil has minimal QT risk. Artesunate IV is safe in emergencies because it clears fast.

The Northern Alberta HIV Program’s 2014 guidelines are still the gold standard. They say: if you’re on a protease inhibitor, avoid artemether-lumefantrine unless you have no other option-and then monitor closely. No guesswork.

What About Artemisinin Resistance?

Artemisinin resistance started in Cambodia in 2008. Now it’s spreading. That means we’re using more lumefantrine, more mefloquine, more combinations. More drugs = more interactions.

Researchers are working on new combos to fight resistance. But until then, the safest path is the one with the least interaction risk. That’s why atovaquone-proguanil is gaining ground. It doesn’t touch QT. It doesn’t rely on CYP3A4. It’s not perfect-it can cause nausea-but it’s much safer for people on multiple meds.

And don’t forget: mass drug administration programs in Africa and Southeast Asia are rolling out antimalarials to entire villages. If we don’t understand these interactions, we could be causing more harm than good.

Bottom Line: Don’t Assume It’s Safe

Antimalarials aren’t like ibuprofen. You can’t just grab them and go. Even if you’re taking them for lupus, not malaria, the risks are real. The heart doesn’t care why you’re on the drug. It only cares about the chemistry.

Every time you add a new pill, ask: Could this stretch my QT? Could this block my liver’s ability to clear my antimalarial? If the answer isn’t clear, get help. Talk to a pharmacist. Run it through a drug interaction checker. Get an ECG.

The stakes aren’t theoretical. People have died from this. Not because they were careless. But because no one told them.

Can I take hydroxychloroquine with antibiotics?

Some antibiotics are dangerous with hydroxychloroquine. Clarithromycin increases QT prolongation risk by nearly 18 times. Azithromycin, often considered safe, has also been linked to Torsades de Pointes. Piperacillin/tazobactam is another risky combo. Always check with a pharmacist before combining any antibiotic with hydroxychloroquine.

Is artemether-lumefantrine safe if I’m on HIV meds?

It’s risky. Protease inhibitors like ritonavir block CYP3A4, which can raise lumefantrine levels and increase QT prolongation. The Northern Alberta HIV Program says this combo isn’t recommended. If no alternative exists, use only under strict ECG monitoring and with dose adjustments.

How often should I get an ECG if I’m on antimalarials?

Get a baseline ECG before starting. If you’re on hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, or lumefantrine, repeat it after 5-7 days. If you have heart disease, are over 65, or are on other QT-prolonging drugs, monitor every 2-4 weeks. For short-term IV artesunate, ECG isn’t needed unless you have pre-existing conditions.

Are there safer antimalarials for people on multiple medications?

Yes. Atovaquone-proguanil has minimal QT risk and doesn’t rely heavily on CYP enzymes. Artesunate IV is also safe in emergencies because it clears quickly. For prophylaxis, doxycycline is a good alternative if you’re not pregnant. Avoid mefloquine and halofantrine entirely if you’re on other heart-affecting drugs.

Why does hydroxychloroquine stay in my system so long?

Hydroxychloroquine is highly lipophilic-it dissolves in fat. It builds up in tissues like the liver and skin, and is released slowly over weeks. Its terminal half-life is 40-50 days. That means even after you stop taking it, it’s still in your body, still affecting your heart. This is why long-term users need ongoing cardiac monitoring.

Can I take antimalarials if I have a pacemaker?

Having a pacemaker doesn’t eliminate the risk. Pacemakers manage slow heart rates but can’t prevent Torsades de Pointes, which is a fast, chaotic rhythm. QT prolongation can still trigger dangerous arrhythmias even with a pacemaker. You still need ECG monitoring and avoidance of high-risk drug combos.

Do supplements interact with antimalarials?

Yes. St. John’s wort induces CYP3A4 and can lower artemether levels, reducing effectiveness. Magnesium and potassium supplements can help if you’re low-but don’t self-prescribe. Too much potassium can also be dangerous. Always tell your doctor about all supplements you take.

What should I do if I experience dizziness or palpitations while on antimalarials?

Stop the medication immediately and seek medical help. These could be early signs of QT prolongation or arrhythmia. Don’t wait. Get an ECG. Even if symptoms go away, the risk remains. Document everything and inform your provider about all drugs and supplements you’re taking.

Eliza Oakes

20 November 2025 - 23:34 PM

Okay but have y’all noticed that every single study cited here is from the US or UK? What about global data? In India, we’ve been using hydroxychloroquine for lupus for decades without mass cardiac collapses. Maybe it’s not the drug-it’s the overmedicated American healthcare system.

Clifford Temple

22 November 2025 - 00:42 AM

LOL so now we’re scared of malaria pills but okay with 17 different prescriptions for anxiety, blood pressure, and sleep? This is why America’s dying. Stop blaming the medicine and start blaming the people who take 12 pills before breakfast.

Corra Hathaway

22 November 2025 - 18:36 PM

Y’all are making this sound like antimalarials are poison… but honestly? They’re just misunderstood superheroes 🦸♀️✨. Yeah, they’re powerful. Yeah, they need respect. But with the right check-in (ECG, electrolytes, pharmacist chat), they’re totally fine. You wouldn’t drive a Ferrari without checking the oil-same logic here. 💪❤️

Shawn Sakura

23 November 2025 - 21:39 PM

Just want to say thank you for this post. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen patients on hydroxychloroquine for years and never get ECGs. This is life-saving info. Please share it with your doctors. I know they’re busy but… this isn’t optional. We need to do better. 🙏

Paula Jane Butterfield

24 November 2025 - 07:52 AM

As someone who grew up in rural India where malaria was a real threat, I’ve seen people take chloroquine like candy-no ECG, no labs, no nothing. But they survived. Why? Because their bodies adapted. We need context. Not every QT prolongation leads to TdP. The risk is real, yes-but so is the fear. Let’s not scare people out of lifesaving meds.

Also, atovaquone-proguanil? Expensive as hell. Not accessible to 80% of the world. We need solutions that work in villages, not just in Boston hospitals.

Simone Wood

24 November 2025 - 10:25 AM

Let’s be real: this is Big Pharma’s way of controlling the narrative. Hydroxychloroquine was demonized during COVID, now it’s being weaponized again under the guise of "cardiac safety." The real agenda? Pushing expensive alternatives like atovaquone-proguanil that only the wealthy can afford. Who benefits? Not you. Not me. Definitely not the Global South.

Swati Jain

25 November 2025 - 22:27 PM

Wow. So you’re telling me that in the US, taking two meds together is a death sentence, but in Mumbai, people take HCQ with antibiotics and live to tell the tale? Maybe your problem isn’t the drugs-it’s the lack of basic healthcare infrastructure. We don’t have ECG machines in every village, but we also don’t have 12 doctors prescribing 30 pills each. Simplicity saves lives.

Florian Moser

27 November 2025 - 20:31 PM

Excellent breakdown. The CYP3A4-lumefantrine-ritonavir interaction is absolutely critical for HIV clinicians to understand. I’ve seen cases where patients were switched from artemether-lumefantrine to atovaquone-proguanil after a QT spike-and their viral load stayed suppressed. This isn’t theoretical. It’s clinical reality. Always check interaction databases before prescribing.

jim cerqua

29 November 2025 - 05:57 AM

THIS IS A MASSIVE COVER-UP. You think this is about heart safety? NO. It’s about control. The FDA, WHO, and big pharma want you to believe that only their expensive, patented drugs are "safe." But chloroquine has been around since 1934. Cheap. Effective. Proven. Now they’re scaring you into paying $150 for atovaquone because they can’t patent the old stuff. Don’t be fooled. The heart risk? Exaggerated. The profit? Real.

And don’t even get me started on how they banned HCQ for COVID while letting people take azithromycin with it-two drugs that BOTH prolong QT. Hypocrites.

Donald Frantz

29 November 2025 - 11:14 AM

Quick question: when you say "QT >500ms is a red flag," is that corrected QT (QTc) or uncorrected? The paper you referenced from Choi et al. uses QTc, but many clinicians mix them up. Also, what’s the cutoff for "increase >60ms from baseline"-is that for all patients or just those with pre-existing conditions? Clarification would help.

Sammy Williams

30 November 2025 - 09:52 AM

Man I just got prescribed HCQ for RA last week. I was gonna ask my doc about the antibiotics I take for acne, but I was too lazy. Now I’m gonna call my pharmacist tomorrow. Thanks for the wake-up call.

Julia Strothers

30 November 2025 - 21:21 PM

They’re lying. The real reason they’re warning about QT prolongation is because they want to force everyone onto mRNA vaccines and biologics. HCQ is a cheap, old drug that doesn’t make them money. That’s why they’re painting it as dangerous. It’s not science-it’s capitalism. And they’re killing people by making them afraid of the only thing that actually works.

Remember the 2020 HCQ trials? All of them were rigged. They gave patients lethal doses. They didn’t monitor. They blamed the drug. It’s all connected.

Erika Sta. Maria

1 December 2025 - 03:19 AM

It’s funny how we fear drugs more than we fear silence. The heart doesn’t scream before it stops. But we scream at pills. We’ve forgotten that nature doesn’t care about our algorithms. HCQ is a plant derivative. Our bodies evolved with these molecules. We’re the ones who broke the balance-by adding 14 more drugs, by ignoring diet, by sleeping 4 hours. The drug isn’t the villain. The lifestyle is.

And yet we blame the pill. Because it’s easier than changing ourselves.

Nikhil Purohit

1 December 2025 - 10:56 AM

Great post! I’m a med student in Delhi and we’re taught to check ECG before starting HCQ in autoimmune patients. But most clinics skip it because of cost. Maybe we need low-cost portable ECGs in rural health centers. Also, potassium levels are rarely checked-people just take diuretics and don’t know why they feel weak. This info needs to be in vernacular too.

Debanjan Banerjee

3 December 2025 - 04:27 AM

As a clinical pharmacist in Kolkata, I’ve reviewed over 200 HCQ prescriptions in the last year. 78% had at least one interacting drug-mostly antibiotics or NSAIDs. We started a simple checklist: 1) ECG? 2) K+? 3) CYP3A4 inhibitors? 4) Alternative? 5) Patient educated? We reduced QT events by 60% in 6 months. It’s not rocket science. It’s basic diligence.

Also, azithromycin + HCQ? Still risky. Don’t believe the "safe" myth. Always document. Always monitor.